Large corporations : how to develop new business models ?

Innovate and develop new business models, these two objectives are the focus of the CDOs of all major companies. However, in large groups, new business models and traditional business models have difficulty coexisting. But what if Schumpeter and Christensen, two theorists of innovation, gave us the keys to do so?

From Schumpeter to Christensen, from the cycle of innovation to disruptive innovation

In 1939, Joseph Schumpeter was the first economist to theorize the importance of innovation and to model its cycles, and today large companies have successfully embraced it: without innovation, a company is doomed to fail. Clayton Christensen, professor at Harvard Business School, introduces in his first book, “The Innovator’s Dilemma”, a work of reference for all startup creators, the concept of ” disruptive innovation “. Christensen’s work is enormous and fundamental. However, it remains unknown in France, difficult to access, disseminated in a multitude of academic articles.

Throughout his academic endeavors, Christensen strived to demonstrate that innovation is not about invention, or simply technological innovation, but rather about the disruption of the business model. It demonstrates how the disruption of the business model is complex to understand for large companies but also how it is fundamental for large groups in a context of accelerating digital revolution.

The change of the business model, the “beating heart” of disruptive innovation

The constant preservation of an optimal level of creativity, capable of renewing both products and services as well as practices and methods is crucial for the sustainability of a company. Especially when it is a large group subject to fierce competition in terms of production but also in terms of financing needs. These innovations improve existing products along an existing performance trajectory. They are called continuous. Disruptive innovations, on the other hand, introduce new dimensions and new performance criteria that are not integrated into the service offer of large companies. These new offers lead to new business models. To support his demonstration, Christensen relies on the “Kodak” case. The New York-based company, a market leader in analog photography and particularly in photographic film, is nevertheless the holder of a patent concerning the digital camera.

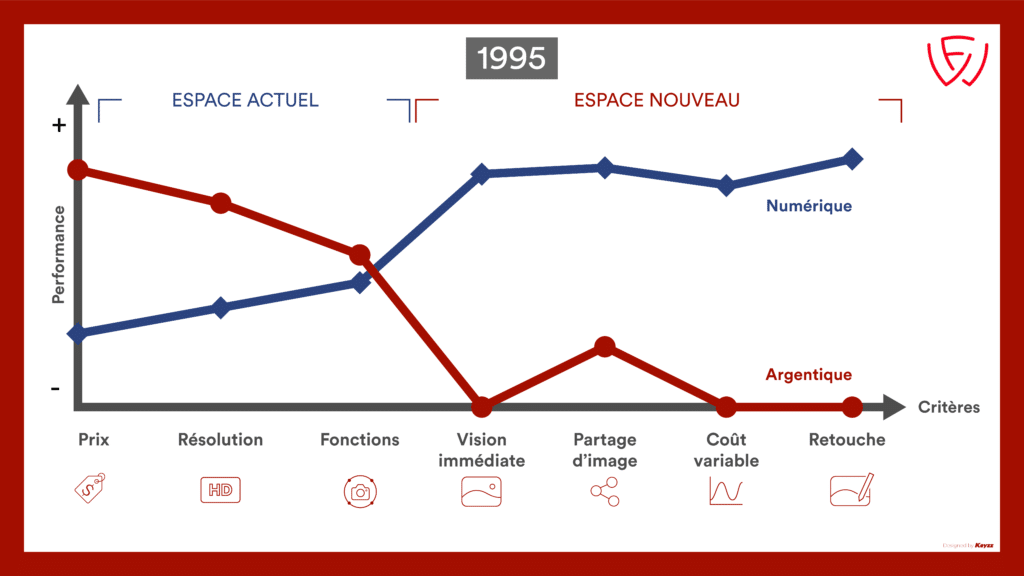

In the diagram above, Christensen shows that in 1995, the technical characteristics of the digital camera did not prompt Kodak to move away from its business model and make the switch to digital.

Despite the potential of the digital market and the undeniable commitment of the century-old American firm, it does not embark on the adventure of digital photography. Not out of timidity as we may be inclined to think, but out of a lack of alignment with the company’s business model. Despite the emergence of the digital market, Kodak continued to sell more and more film each year until 2000. Finally, digital developments are considered too big and that they may threaten Kodak’s business model. This results in a conflict between the new and old activity. The company had become trapped in its business model.

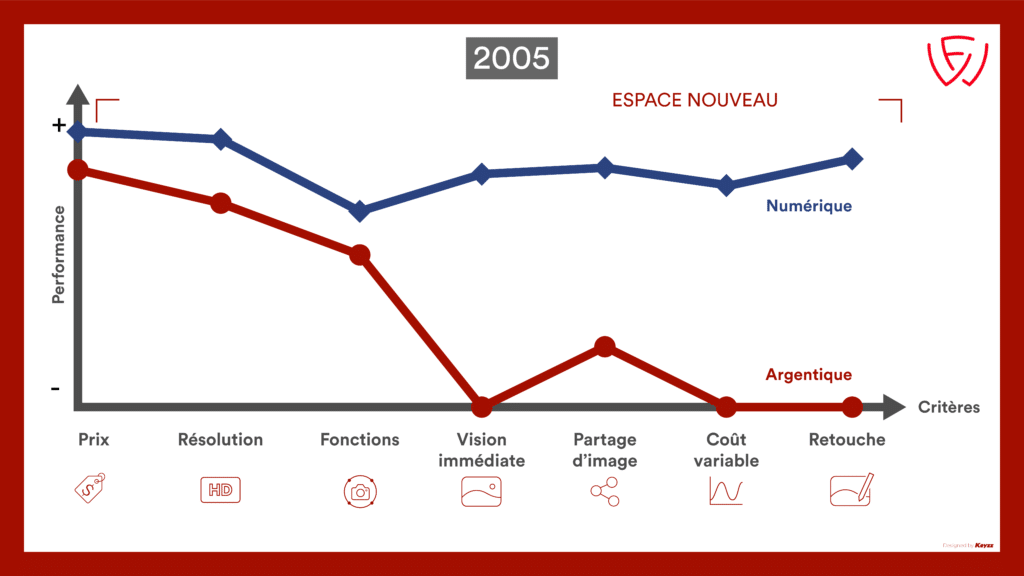

In 2005, 10 years later, it was quite clear that digital has surpassed film in every respect, but it was too late for Kodak to react and focus on the digital market. On 19 January 2012, the company filed for bankruptcy. Kodak and its US subsidiaries are seeking Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in order to restructure. A sign of its struggles is that the company had only 17,000 employees at the time of filing for bankruptcy, compared to 64,000 about ten years earlier.

The corporate startup studio helps large groups to redefine innovation

“This is partly where the help of a corporate startup studio can be fundamental for a large group,” comments Gilles Debuchy, founder of Wefound. During the ideation phase, corporate startup studios help large companies to imagine new business models, because generally if groups are aware of their needs in terms of disruptive innovation, they have difficulty making realistic projections. “From the ideation phase, we help to identify new business models that are compatible with the Group’s historical culture or its strategic objectives,” continues Gilles Debuchy.

Exiting the infernal downward spiral of competition that consumes all available financial resources

Christensen goes further in his argument in favor of innovation by developing the example of Kodak, whose historical business model found digital photography unattractive. Admittedly, according to Christensen, the old model is sentenced to term, but this term is uncertain. And meanwhile, the traditional business model provides the bulk of the company’s resources. The new model represents the future but will not provide serious and viable resources until uncertain times. In this context, according to Christensen, investors and financial partners will demand that all investments be concentrated on the old business model to fight in a context of strong competition. And this competition will be made even tougher with the introduction of new entrants, disruptive as they are wont to be.

“May the circle be unbroken”.